Report: Decolonize Birth 2018 Conference

by Koyuki Smith

Two weekends ago, I attended the third annual Decolonize Birth conference in Brooklyn, NY. Decolonize Birth is run by Ancient Song Doula Services, a community-based full-spectrum doula collective and training organization founded by Chanel Porchia-Albert. This year’s conference title was "Addressing the Criminalization of Black and Brown People within the Healthcare System."I was only able to attend the second day of the two-day conference, and this year I chose to attend as a volunteer, which meant that my day was full of finding cables, rearranging chairs, and ferrying rolls of tape and pairs of scissors from one part of the conference hall to another. Because I was only present for one day, and because my attention was partially occupied by conference work on that day, I can’t pretend to be able to provide a full accounting of all that was said and accomplished, particularly in comparison with those who were present for the entire time and not working while there. However, I can give a general sketch that will be of interest to those who were not able to attend at all.

If you are interested in learning more about these matters, I urge you to set aside some time - plenty of time - to follow all of the links in this post and read all of the material in each link. Taken together, these texts offer an excellent picture of the issues in the field and the work being done.

While there were many many strands of thought introduced over the course of the conference, in my mind they all tended towards two central takeaways.

1) The webs entangling birthing people of color are deeply rooted, wide ranging, complex, and brutal.

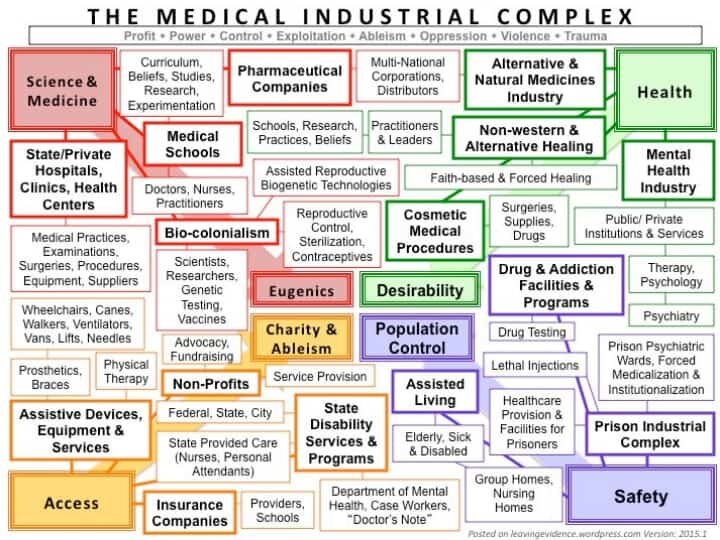

(This is of course true for all birthing people and all people of color - and indeed all people living under modern industrial capitalism - but the situation for birthing people of color is particularly enmeshed, intractable, and malicious.) The conference title speaks to this complexity, explicitly linking the criminal justice system and the health care system. This is a connection that many people might initially find to be surprising. My husband, for example, who is himself an attorney specializing in criminal and immigration defense here in New York City, was at first puzzled when he heard that Erin Cloud of the Bronx Defenders was a speaker at the conference: “What do the Bronx Defenders have to do with birthing?”The truth is, of course, that the health care system and the legal system are so enmeshed as to sometimes become indistinguishable. This enmeshment weighs particularly on those whose health care and living conditions are extensively, specifically mediated by the state and who lack the power that might allow them to bypass this mediation. Consider the following presentation titles, which illustrate the point vividly: “Child Protective Services: The New Norplant” (Erin Cloud, Bronx Defenders); “Removing Prosecutors, Investigators, Caseworkers, and Doctors From The Womb” (Lynn Paltrow and Aarin Michelle Williams, National Advocates for Pregnant Women); “Advancing Accessibility of Doula Care Through Medicaid Reimbursement” (Chanel Porchia-Albert, Ancient Song Doula Services); “The Role of Coercion, Threats, and Force in the Criminalization of Black and Brown Pregnant Folks” (Indra Lucero, Birth Rights Bar Association; and China Tolliver, Black and Latina Breastfeeding Week of Denver, CO).Here are two maps of these of systems/webs/traps.This first map is from Jessica Roach (pictured), the founder of ROOTT in Columbus, OH, speaking on the panel entitled “Black Mamas Matter Alliance Discusses Racial Disparities in Maternal Mortality.” She showed this map in the context of explaining how negative structural determinants persist even when negative social determinants might be expected to be “resolved” or absent. She used her own case as an example. She is an RN, highly educated, in a relatively high socioeconomic bracket, and married to a white man - and thus apparently “free” of many of the negative determinants weighing upon birthing people of color. As a birthing patient, however, she found that she was subject to the oppression and abuse built into the structure of the medico-legal system despite having the social determinants that would seem to allow for escape. (Photo courtesy Virginia Bechtold.)This second map, credited to transformative justice and disability justice activist Mia Mingus, was part of Olivia Ahn’s presentation “Abolition Now: Doulas as Catalysts in Carceral Health.” (Ahn was kind enough to share the slide with me; it's also available here.) It illuminates the connections between institutions, ideas/ideals, services, objects, and individuals within the modern medical industrial complex. For those who haven’t spent time thinking about these forces, this map may at first seem hyperbolic or paranoid. If you are feeling that way, take some time to break it down. Examine just two or three neighboring boxes at a time and explain to yourself how they are connected - it should be pretty straightforward, nothing convoluted or surprising. Repeat this for various parts of the map, and you will see that each individual connection makes logical sense. Operating together, all of these interconnections (many of which seem relatively value-neutral) result in a larger, more menacing whole, whether or not they were intended to do so. Remember, no intentional “conspiracy” is necessary in order for an organized, directional system to coalesce. (That said, it’s also true that parts of how this particular system bears upon black and brown bodies are entirely intentional, cf. The New Jim Crow.)

2) Recognition of and return to the cultural care traditions that have always existed within black and brown communities is key to rebalancing and redressing systems of medico-legal oppression. These traditions are under constant threat of being extinguished and/or coopted by the white power structure.

audre lorde

Consider these presentation titles: “Student Midwifery 101: Black Midwives Will Save Us” (Efe Osaren, DoulaChronicles); “Storytelling as Activism: Using Birth Stories to Advance Birth Justice in NYC” (Kayhan Irani, Artivista; and Nicole Jean Baptiste, Sese Doula Services); “Birth Outside the Margins: Using Our Ancestral Tools to Free Us” (Makeda Rambert, Black Star Birthing Project).I was lucky to have been assigned to support Makeda Rambert's presentation, and was thus able to watch the whole thing. Later, she too was kind enough to share some of her slides with me. This Audre Lorde quote explicitly states a bedrock truth about the society in which we live: all of its systems treat as “normal” what is actually a relatively small slice of the population, leaving everyone else on the conceptual margins of policy and practice.“Decolonization” is the process by which an individual or group rejects the definition of itself as marginal in relationship to a conceptual norm that has been forced upon them from the outside.For black communities in the United States, decolonization will include the relearning, strengthening, and protecting of traditional practices, including gardening, herbalism and other folk medicine, and conjure. These practices, Rambert points out, are “so frequently coopted and demonized that it is easy to think that there is no distinct culture,” but they are the birthright of African American people.In small-group discussions, participants unpacked some of the tangled-up baggage accompanying these understandings. Some participants spoke of their own knee-jerk rejection of traditional care practices as being superstitious, ignorant, or embarrassing. Some participants spoke of their experiences in nursing or midwifery school, being surprised and dismayed that during surveys of traditional herbal medicine, traditional African or African-American practices were either excluded or presented as though they were white Western practices. Medical professionals discussed the difficulty of deploying any kind of care at all under the evaluative white (colonizing) gaze of their colleagues and supervisors. Doulas discussed the difficulty of offering culturally-appropriate, traditionally-grounded support to clients caught inside the systems illustrated in the maps above. Many spoke of the inevitable drive towards profit and its negative effects on traditional practices.In addition to Rambert’s presentation, I was also lucky enough to be assigned to support Olivia Ahn’s “Abolition Now: Doulas as Catalysts in Carceral Health.” Towards the end of Ahn’s talk, which dealt with the Ancient Song Prison Doula Services and Re-Entry Program, a participant asked how she could become involved with similar work in her community. This is in essence the question that most people arrive at after reaching a clear understanding of these issues: What can I do? How can I help? Ahn’s answer was instructive: locate an organization like Ancient Song that is devoted to full-spectrum doula work and is, like Ancient Song, run by a black woman.

This, in the end, is the fundamental understanding communicated by Decolonizing Birth: it is time (far, far past time) to center the perspectives and experiences of those who have been forcibly marginalized, often at great risk to their bodies and minds. It is time to be very quiet as they speak, very respectful as they educate, and very supportive and hard-working as they show us the way forward.

SaveSaveSaveSaveSaveSaveSaveSaveSaveSaveSaveSaveSaveSaveSaveSaveSaveSaveSaveSaveSaveSaveSaveSaveSaveSaveSaveSaveSaveSaveSaveSave